The United States of America has a long history of attracting individuals from all over the world offering them diverse opportunities, and Georgians have been no exception to this. While it is impossible to identify the very first Georgian immigrant to the United States, Georgians have been migrating to the U.S. for many years, contributing to the development of diverse fields through their hard work and dedication.

This exhibition is a tribute to Georgians who have left their notable footprint in the United States of America. It recognizes the contributions of those who have left their homeland to live and work outside our country’s borders.

In the 20th century, Georgian immigrants had different reasons for leaving their homeland, and their backgrounds and circumstances varied widely. These factors influenced their experiences in the United States. The process of Americanization and their success in a new country differed from one individual to another, as did their quality of life and achievements in their new homeland.

Alexander Kartveli; George Balanchine; George Koby; Giorgi Papashvily; Tamara Tumanova; Prince Machabeli; Prince Gurieli-Chkonia, and Georgian horsemen, this is just a short list of outstanding Georgians who serve as a testament to the significant contributions of Georgian community to the United States of America.

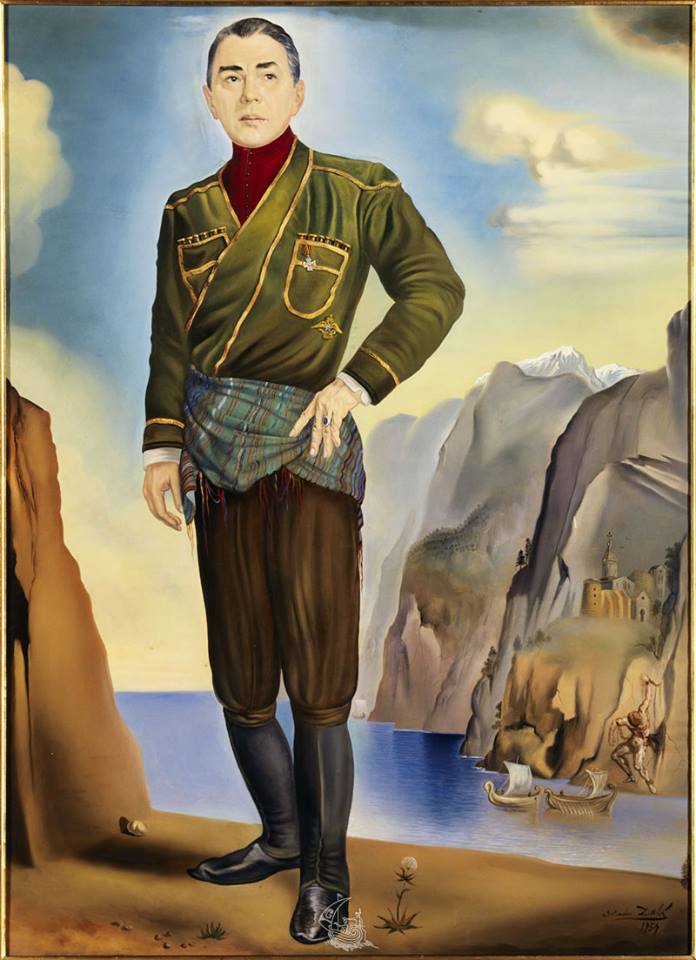

General Shalikashvili achieved the highest ranking position in the US military. He joined the United State Army as a private, served in every level of unit command from platoon to division, and rose to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As a Georgian he was also the first foreign-born Joint Chiefs Chairman. He was also the first draftee and first graduate of Officer Candidate School to hold the position.

John Malchase David Shalikashvili was born in Warsaw, Poland, a descendant of the Georgian noble house of Shalikashvili. His father, Prince Dimitri Shalikashvili served in the army of Imperial Russia, and was a grandson of Russian general Dmitry Staroselsky. The princely “Schalikashvili” family of Georgia traces its lineage back at least to the year 1400.

In 1952, when Shalikashvili was 16, the family immigrated to Peoria, Illinois. He spoke little English when he arrived in Peoria but learned the language by watching American movies. He attended Bradley University in Peoria and earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1958.

After graduation he received a draft notice and entered the Army as a private. He later applied to Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1959. Shalikashvili served in various Field Artillery and Air Defense Artillery positions as a platoon leader, forward observer, instructor, and student, in various staff positions, and as a battery commander. He served in Vietnam as a senior district advisor from 1968 to 1969, and was awarded a Bronze Star with “V” for heroism during his Vietnam tour. In 1970, he became executive officer of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Field Artillery at Fort Lewis, Washington. Later in 1975, he commanded 1st Battalion, 84th Field Artillery, 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis. In 1977, he attended the U.S. Army War College and served as the Commander of Division Artillery for the 1st Armored Division in Germany. He later became the assistant division commander. In 1987, Shalikashvili commanded the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, where he oversaw a “high technology test bed” tasked to integrate three brigades—one heavy armor, one light infantry, and one “experimental mechanized”—into a new type of fighting force.

One of his most notable achievements was directing the relief program, Operation Provide Comfort. In April 1991 Lieutenant General Shalikashvili went to northern Iraq to avert a humanitarian crisis following the end of the first Gulf War. The Iraq army forced over 500,000 Kurds into the inhospitable mountains along the Turkish border. Lacking food, water, and shelter, approximately 1000 Kurdish men, women, and children were dying each day. Shalikashvili led a massive relief mission to rescue the Kurds. The operation eventually involved 35,000 soldiers from 13 countries as well as volunteers from over 50 Non-Government Organizations working together effectively. The operation first delivered life-saving supplies and then turned the effort to establishing safe refuge. His troops worked with relief agencies to build the camps while also confronting threats from hostile Iraqi army forces. Shalikashvili met with Iraqi forces, warning them of the risks of attacking the relief effort. Hostilities were avoided, leaving the coalition troops to focus on assisting the displaced. Shalikashvili’s command saved lives, brought order, and allowed the more than 500,000 displaced to return to their homes within several months. General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs at the time, would later say that General Shalikashvili had worked “a miracle.”

In August 1991 General Powell recognizing Shalikashvili’s leadership skills and organizational ability, called him back to Washington, D.C., as his assistant. Shalikashvili had demonstrated great diplomacy and logistics skills and Powell noted that he was able to operate in new conceptual territory with ease. In 1992 Shalikashvili was named Supreme Allied Commander Europe, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). His knowledge of Europe and ability to speak Polish, Russian, and German played a role in this assignment.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton appointed Shalikashvili as the 13th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. President Clinton referred to him as “General Shali,” a soldier’s soldier. The president, in calling him General Shali, followed the affectionate name used by the general’s staff. As chairman, Shalikashvili advised President Clinton on military and humanitarian missions to Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia, and the Persian Gulf. He oversaw more than 40 operations and sought greater integration of military and civilian agencies operating jointly to respond to humanitarian crises. He also continued the efforts of his predecessor Colin Powell at improving joint operations with the various military branches. Shalikashvili had the difficult task of reducing the military budget to realize a “peace dividend.” This included cutting unneeded weapons systems and the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure Act. He completed his chairman’s tour in 1997 and retired. At his retirement ceremony President Clinton awarded him the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award recognizing the General for working “tirelessly to improve our Nation’s security and promote world peace.

General Shalikashvili visited Georgia together with his brother, a retired colonel from the US Special Forces Othar Shalikashvili, in May, 1995. While in Georgia, they travelled to Kakheti region, to the home region of their ancestors – Gurjaani. They also met with the then head of Georgian state, Eduard Shevardnadze.

Following retirement, Shalikashvili was an advisor to John Kerry’s 2004 Presidential campaign. He was a visiting professor at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, and served in various capacities with a number of businesses. In 2006 the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) launched the John M. Shalikashvili Chair in National Security Studies to recognize Shalikashvili for his years of military service and for his leadership on NBR’s Board of Directors.

Shalikashvili died at the age of 75 on July 23, 2011, at the Madigan Army Medical Center in Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Upon his passing, President Barack Obama said that the United States lost a “genuine soldier-statesman,” adding in a statement that Shalikashvili’s “extraordinary life represented the promise of America and the limitless possibilities that are open to those who choose to serve it.”

Former president Clinton pointed out that “Gen. Shali” made the recommendations that sent U.S. troops to Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia, the Persian Gulf and a host of other world hotspots that had proliferated since the end of the Cold War. “He never minced words, he never postured or pulled punches, he never shied away from tough issues or tough calls, and most important, he never shied away from doing what he believed was the right thing,” Clinton said.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said in a statement that he relied on Shalikashvili’s advice and candor when he served as Clinton’s chief of staff during the foreign policy crises in Haiti, the Balkans and elsewhere. “John was an extraordinary patriot who faithfully defended this country for four decades, rising to the very pinnacle of the military profession,” Panetta said. “I will remember John as always being a stalwart advocate for the brave men and women who don the uniform and stand guard over this nation.”

The then chairman, Adm. Mike Mullen, said Shalikashvili “skillfully shepherded our military through the early years of the post-Cold War era, helping to redefine both U.S. and NATO relationships with former members of the Warsaw Pact.”

John Shalikashvili left a proud legacy for all Georgians.

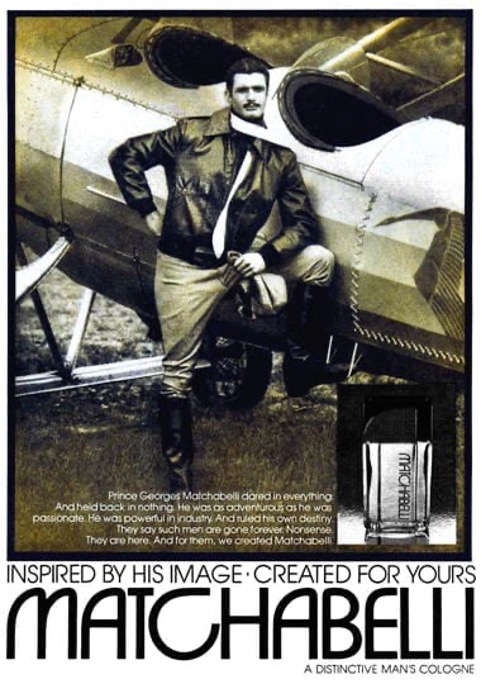

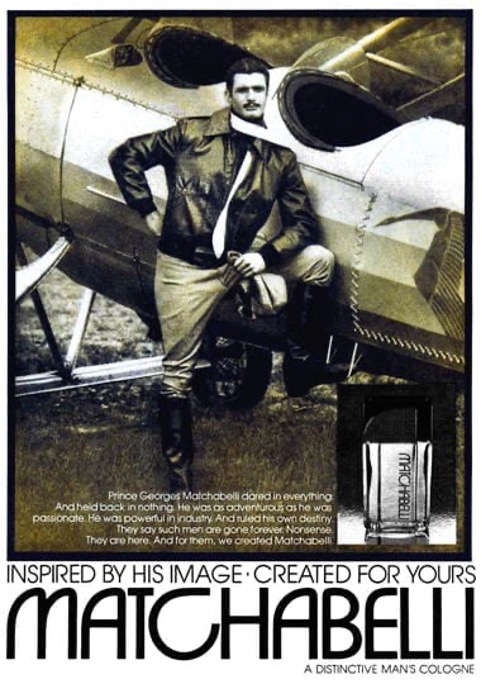

Prince Georges Vasily Matchabelli was born in Tbilisi – formerly known as Tpilisi or Tiflis – the capital of the eastern European country of Georgia. The Matchabelli (Machabeli) family had large estates in the Samachablo (literally ‘of Machabeli’) region of Inner Kartli (Shida Kartli) Georgia. Georges, who also described himself as being from Tamarasheni, received a general education at the Tbilisi College for Nobility, followed by engineering at the Frederick William University in Berlin – today known as the Humboldt University – before returning to Georgia to help with the family mining interests. In 1917, he married the Italian actress Norina Gilly [1880-1957] – stage name Maria Carmi – in Stockholm, Sweden.

When Georgia became a republic in 1918 – following the Russian Revolution of 1917 – Matchabelli offered his services to the new government and was made Minister Plenipotentiary to Italy. He moved to Rome in 1918, but the posting came to a close in 1921, when Georgia’s independence was ended by the invasion of the Red Army. To make matters worse the new Soviet government confiscated the Matchabelli estates and mining interests.

In 1923, Norina was engaged to producer Morris Gest [1875-1942] to perform in an American revival of ‘The Miracle’ – a theatrical spectacular written by her first husband Karl Vollmöller [1878-1948] – repeating her London performance of 1912 and she moved to New York.

Georges followed her to New York from Italy in 1923 and although Norina terminated her contract with Gest in April 1924 – and then began legal proceedings against him – the couple remained in New York and became involved in the city’s social and cultural life.

To help with their finances Norina did an endorsement for Pond’s creams in 1924 and Georges leased a store at 545 Madison Avenue from Douglas L. Elliman & Co. and opened ‘Rouge et Noire’ (Red and Black), an antiques, gifts and imported novelties shop. Norina eventually patched things up with Gest and appeared in the 1929 Detroit production of ‘The Miracle’. By the Georges had moved on from antiques and was busy with a new venture, a perfume company.

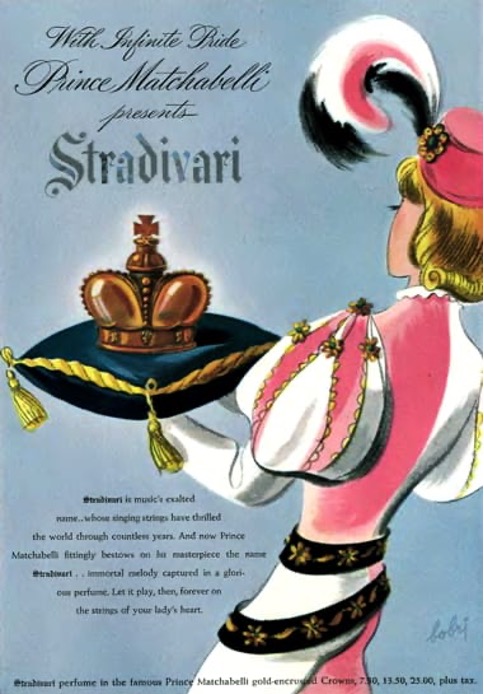

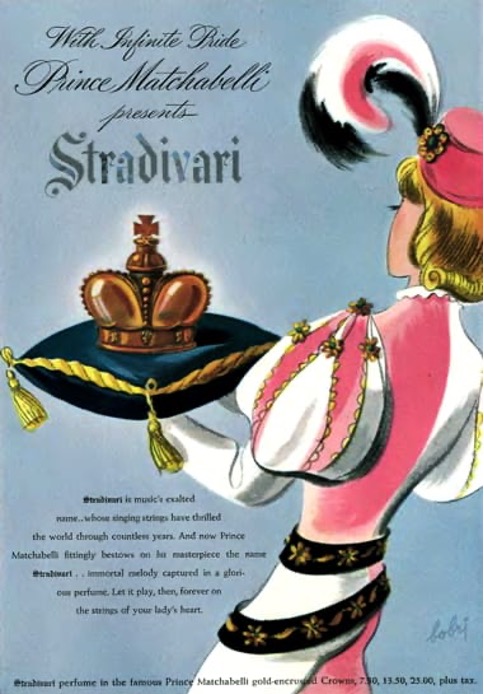

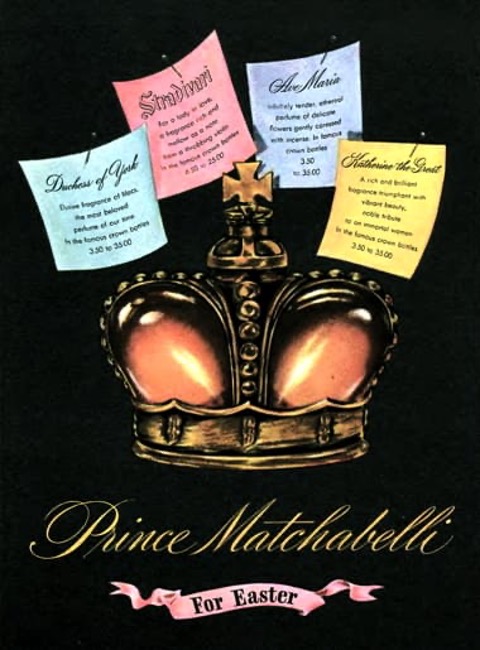

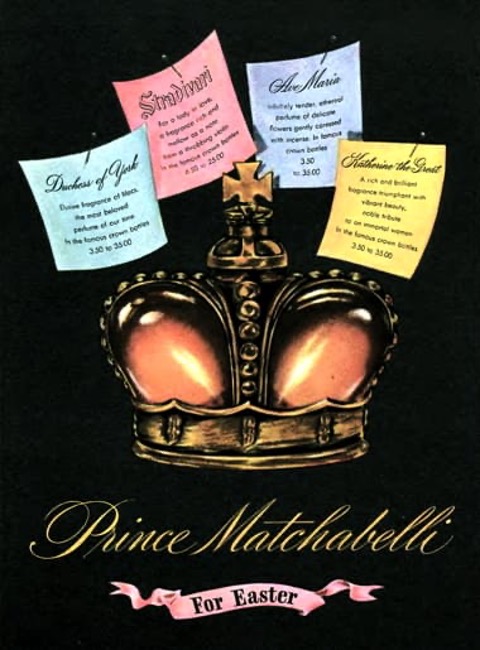

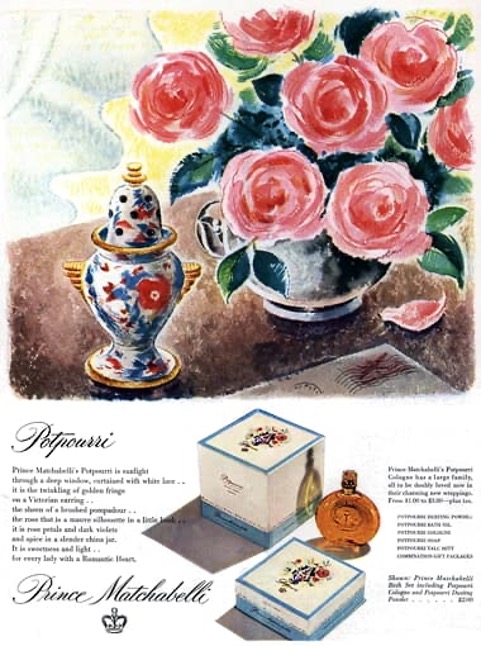

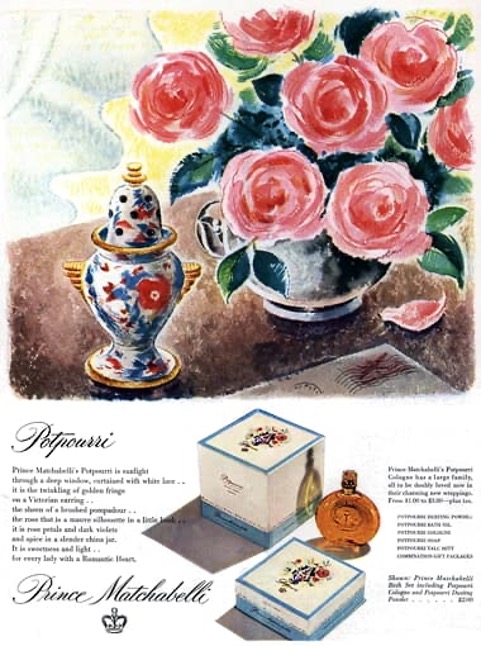

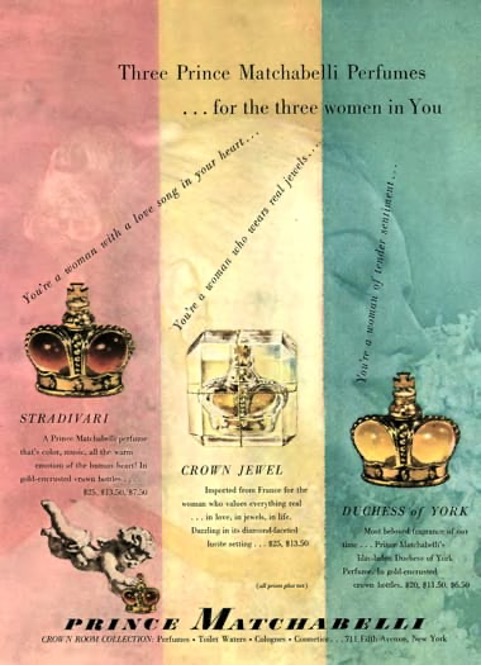

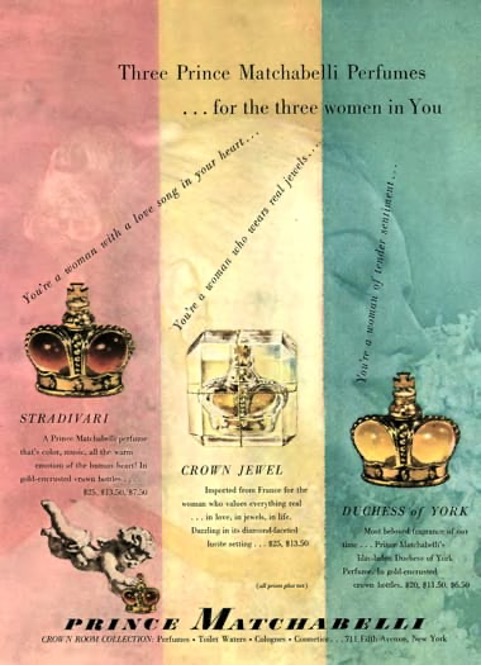

Prince Matchabelli Perfumery Company

In 1926, Georges borrowed $4,000 and together with Norina established the Prince Matchabelli Perfumery Company. Operations began modestly with Georges making special perfumes in the basement of the Madison Avenue store for noted personalities such as Gloria Swanson and Dolores Costello as well as society women such as Mrs. William Randolph Hearst. He also made personal appearances at Hickson’s in their Fifth Avenue store and others in various American cities either selling his own perfumes – Princess Norina and Ave Maria, named in honor of his wife and her role in ‘The Miracle’ – or blending fragrances individually for Hickson’s clients. In 1927, he began appearing on a perfume counter at Bergdorf-Goodman at 754 Fifth Avenue selling perfumes he was making in his laboratory on East 60th Street. Sales to other department stores followed.

The business expanded rapidly, helped along by the company’s association with royalty – where possible Matchabelli hired other Georgian and Russian émigrés with connections to noble houses – and the personal style of Prince Matchabelli himself.

Prince Matchabelli affects to be very particular where his perfume is marketed, and has refused to let several places handle it because he felt their social tone was not just right. Meeting a woman for the first time, he often politely informs her that her perfume is unbecoming and sends her one of his own. If she is still using her old kind the next time he sees her, he says, “You have not been faithful to me.” His business nets a quarter of a million a year, they say, and has grown out of its cellar to a laboratory in Fifty-sixth Street where sachets, powders, lipsticks, eye-shadows, and soap are made. He employs no salesmen. Every spring and fall he goes on the road himself. With his gardenia, his bows and courtly airs, and his visiting card with its embossed seal he creates an extraordinary impression on buyers who have never before trafficked with a genuine, hundred-per-cent prince.

(The New Yorker, 1930, p. 13)

According to numerous reports, Georges had a long-standing interest in perfumery which had begun in Berlin where he had blended perfumes for friends.

While studying in Berlin to be a mining engineer he became interested in perfumes through the plight of a lady friend who could not find the odor she desired. His chemistry professor, by advice and precept, enabled him to make the blend and he became interested in the science. On coming to America, where he opened an antique shop, he devoted his spare time to delving in the preparation of perfumes and found it both fascinating and more profitable than antiques. So he went on with the study of chemistry and odors, going into it thoroughly, as will be seen by the fact that for two years he has attended the night courses on perfumes and cosmetics conducted by Professor Wimmer at the New York College of Pharmacy, Columbia University (AP&EOR, 1927).

However, Matchabelli was not the only émigré to get into perfumes and the idea of establishing a perfume business may have come from his contacts in Paris. There, a number of Parisian fashion houses started by Russian émigrés had begun developing perfumes after Chanel introduced Chanel No. 5 in 1921. The list included: Prince Youssoupoff (Yusupov) the founder of Irfé who began creating scents in 1926; Grande Duchess Maria Pavlovna, the founder of Kitmir who introduced her fragrance ‘Prince Igor’ in 1928; and Baroness-Hoyningen-Huene, the founder of the Yteb, who began making perfumes in 1929 (Vassiliev, 2000).

The growth of the Matchabelli company necessitated a series of moves, first to East 60th Street, then to 686 Lexington Avenue, and on to 160 East 56th Street in 1929. In 1929, Matchabelli also established a Parisian factory at 58 Rue de Meudon, Clamant and opened a showroom in the Hotel George V at 31 Avenue George V, Paris. This luxury hotel, completed in 1928 by the American businessman Joel Hillman [1866-1951], catered primarily to wealthy American clients. It was probably recommended to Matchabelli by his press agent, Benjamin Sonnenberg [1901-1978], who had been working to promote the Hotel George V since 1926. Matchabelli would not stay there for long. In 1930, he opened new showrooms at 26 Rue Cambon, Paris, opposite Chanel.

The Great Depression of the 1930s affected sales and may have been the reason behind the addition of new perfume bottle colors (blue, black, rose, etc.) in 1930, and the decision to begin selling perfume in smaller, cheaper, one and two dram sizes. These were more affordable and opened Matchabelli to a wider number of buyers. In 1935, Matchabelli also boosted sales by advertising in newspapers for the first time on its own right. Previously this had only been done in cooperation with department stores and other dealers.

In June, 1935, a new Matchabelli showroom was opened on the eleventh floor of the former National Broadcasting Building at 711 Fifth Avenue, New York. Occupying almost 1,700 square meters (18,000 square feet) it included space for offices, manufacturing facilities and showrooms. Unfortunately, Georges Matchabelli was not there to see it, having died from pneumonia at the end of March.

Cosmetics

Prince Matchabelli is best known for its perfumes and colognes, but the company began selling cosmetics soon after it was established. There are some suggestions that early products included a skin lotion but, in general, most cosmetic lines were associated with bathing or were a type of make-up.

Belila, a liquid whitener for the arms and shoulders, and Bronzina, a red liquid that turned beige on application to give the skin a tanned appearance, were both introduced in 1929. By then Matchabelli was also selling lipsticks; triple, double and single compacts in attractive black containers with a gold crown on them; soaps; face powders; and a pine essence for the bath. It seems very unlikely that Matchabelli was making most of these lines but rather was assembling, packing and distributing items manufactured by private label firms. Product packaging was extremely important to the success of the business and a great deal of attention was given over to it. Other color cosmetics such as mascara and eyeshadow were added soon after.

In regard to cosmetics, two early Matchabelli perfumes are worth mentioning. The first was Duchess of New York (1929) which outsold all other Matchabelli fragrances in the early 1930s by a wide margin (Stone, 1935, p. 201) and was later used as the basis for a make-up line; the second Abano (1931) became the basis for a number of lines.

Abano

Although created originally as a perfume, Abano is best known as the fragrance for Abano Bath Oil, introduced in 1933. This was a very popular product, predating Estée Lauder’s Youth Dew Bath Oil by two decades. Matchabelli also used Abano as the fragrance for Tanabano (1933) a sun oil and successive owners of the firm added other lines including Abano Dusting Powder, Abano Cologne Sticks (1950), Abano After Bath Cologne (1954), Abano Spray Mist Cologne and Abano Dry Skin Treatment Bath Oil (1961).

New owners

In 1935, Georges succumbed to pneumonia in his apartment at 320 East 57th Street. Norina was at his bedside when he died, despite having divorced him in 1933. After Georges’ death the presidency of Matchabelli passed to her and the company was put into administration. Georges owned about 60% of the American business and also had some shares in the French branch. Beneficiaries of his estate – made up of cash, shares and some mortgaged French real estate – included: Ilo Vasilievich Matchabelli, a brother residing in Leningrad; Nina Dvingaradze, a sister living in Paris; and Thamar Matchabelli, a niece also from Paris. Most of the inheritance was to go to Ilo Matchabelli but Norina put in a claim for US$30,000 and one-third of the estate (New York Post, April 30, 1935).

Alexander Kartveli, American aeronautical engineer, innovator and advisor to NASA of Georgian descent. Kartveli designed the A-10, P-47, F-105 and F-84 in addition to other experimental X-planes.

Alexander Kartveli, born Alexander Kartvelishvili,: ალექსანდრე ქართველიშვილი) (September 9, 1896 – June 20, 1974) was an influential aircraft engineer, a pioneer in American aviation history and an early technology innovator. Kartveli achieved important breakthroughs in military aviation and design. He is considered to be one of the most important aircraft designers in the U.S. and world history. Yet, regrettably, Kartveli is unknown to most Americans and Georgians.

Kartveli’s personal journey parallels a professional career made up of persistent design contributions, whose impact and timing take on a magical quality – and whose contribution velocity increased with the challenges of his era. He ventured out of his native Georgia fleeing the Bolsheviks. Leaving behind his family members, Kartveli, along with his mother, escaped turmoil and oppression to pursue a boyhood dream to design aircrafts in the nascent field of aviation – an industry that resembled the freewheeling days of the early Internet. While in an aviation school in Paris, one of Kartveli’s plane designs set the world speed record. He earned a huge respect and reputation on the Paris aviation scene in the 1920’s, and, eventually, met the American aviation entrepreneur, Charles Levine. Soon thereafter, Kartveli came to the United States as a penniless immigrant to oversee the engineering and design at Levine’s venture-financed aircraft manufacturing company.

“It is possible with reasonable advancement of our knowledge to go beyond the moon to Venus and Mars, provided we retain enthusiasm, enterprise and daring.” — Alexander Kartveli, Burlington Daily Times-News. March 26, 1958

Much like so many other accomplished inventors and entrepreneurs, Kartveli’s journey included a personal reinvention forged through the pain of alienation, emigration and resilience in the face of failed business ventures. Kartveli’s life is an inspiration to present-day inventors and entrepreneurs, who face the impossible task of challenging conventional thinking, while taking great personal risk. He embodies the modern spirit of innovation and boldness of vision needed to break down borders and boundaries. These are the common traits of a short list of important technology founders, who opened our eyes to the potency for individuals to innovate by uniting head and hand.

Integral to his story is the contrast between Kartveli’s creativity and enterprising spirit and the global menace of hate and tyranny that threatened the Western civilization during his lifetime. While no single design concept by Kartveli can be described as radically novel, his overall contributions amount to the global legacy that goes far beyond the value of any single wing design or futuristic spacecraft concept. Today, we are learning more about his struggle with persistent surveillance motivated by fears of espionage and kidnapping. Ultimately, his personal qualities outshined his challenges, and his prompt seizure of opportunity created a generational arc of excellence that is just beginning to be acknowledged. It is unthinkable to imagine the course of history had Kartveli (and others like him) not escaped the tyrannical Axis grip.

Innovators like Kartveli helped win the war, defeat tyranny, and pave the way for entrepreneurial engineers to capitalize on technology’s transformative potential. Today nearly every society on earth feels the impact of technology in every industry. Starting from the early 20th century, when innovators like Karveli gained influence, a whole class of leaders emerged as a new breed of designers and engineers, who combine the scientific method with an excessive orientation towards possibilities.

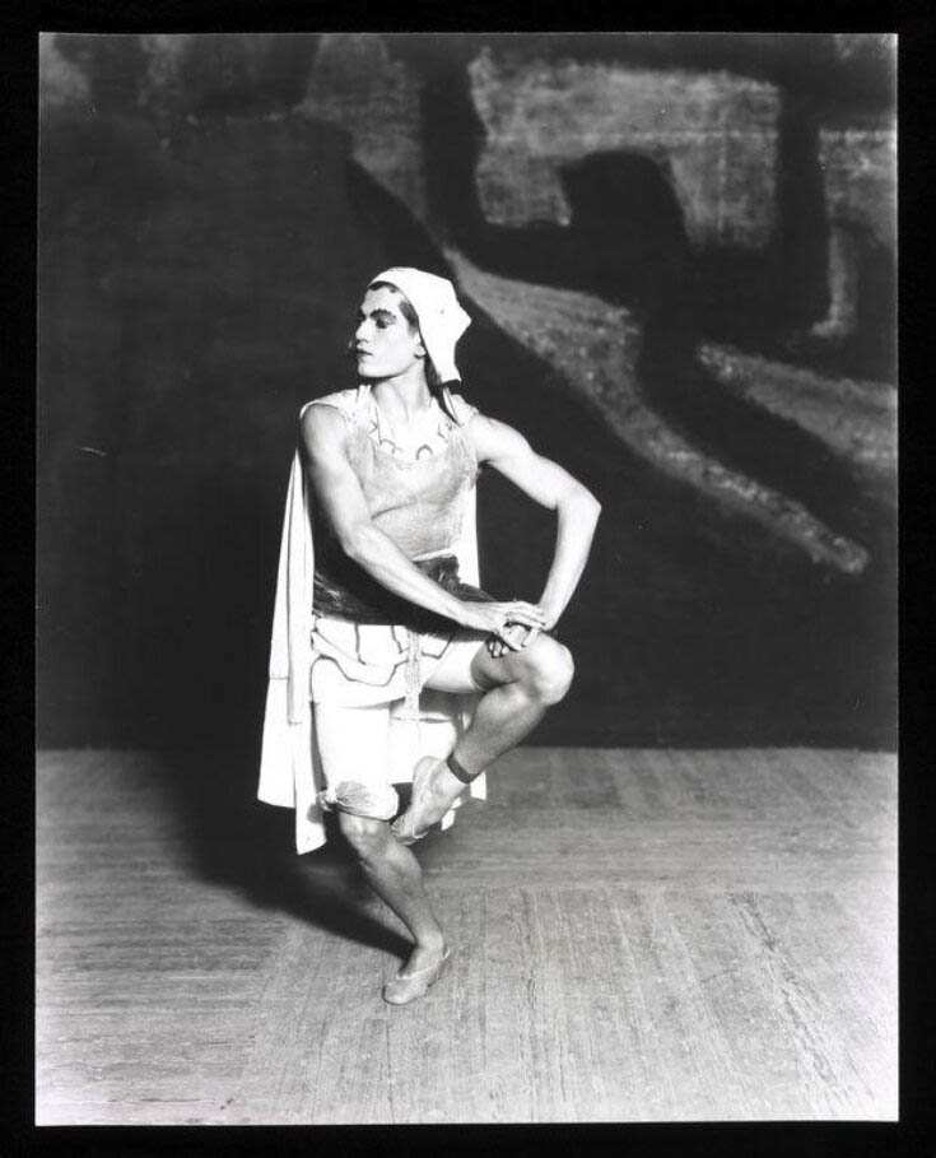

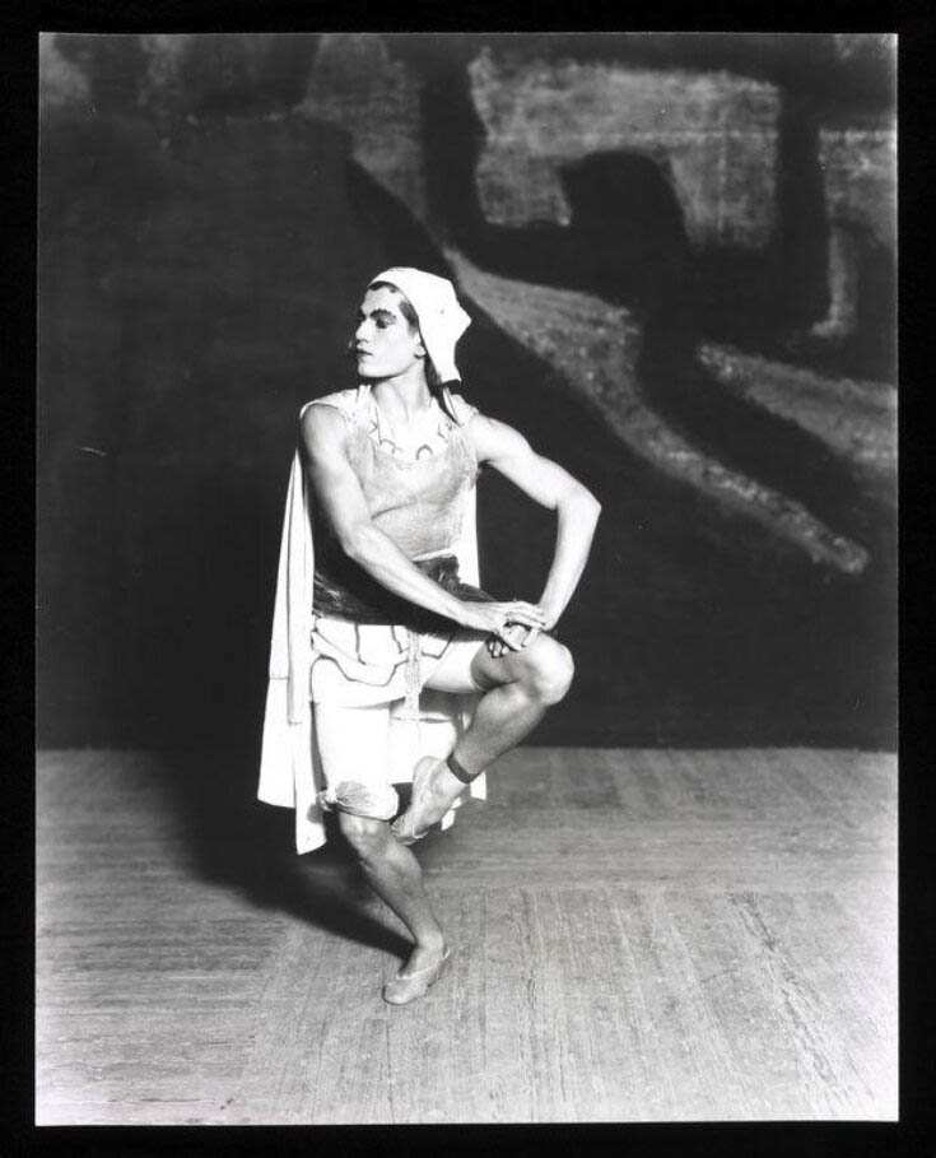

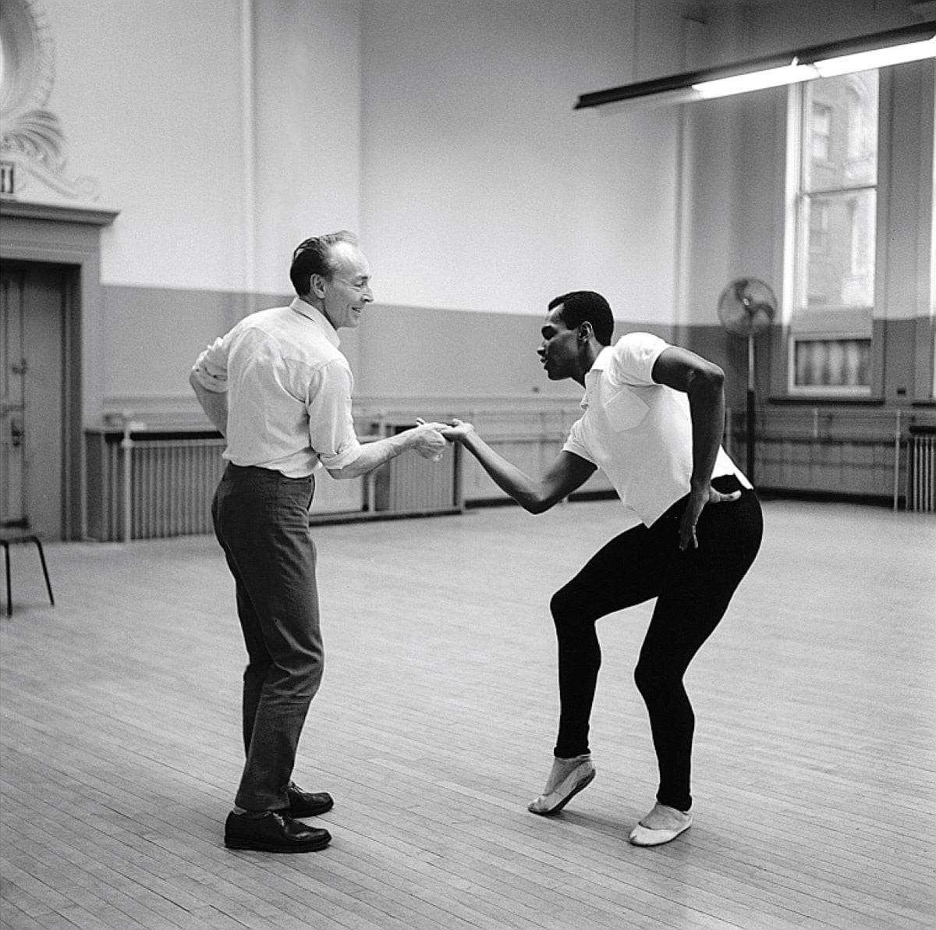

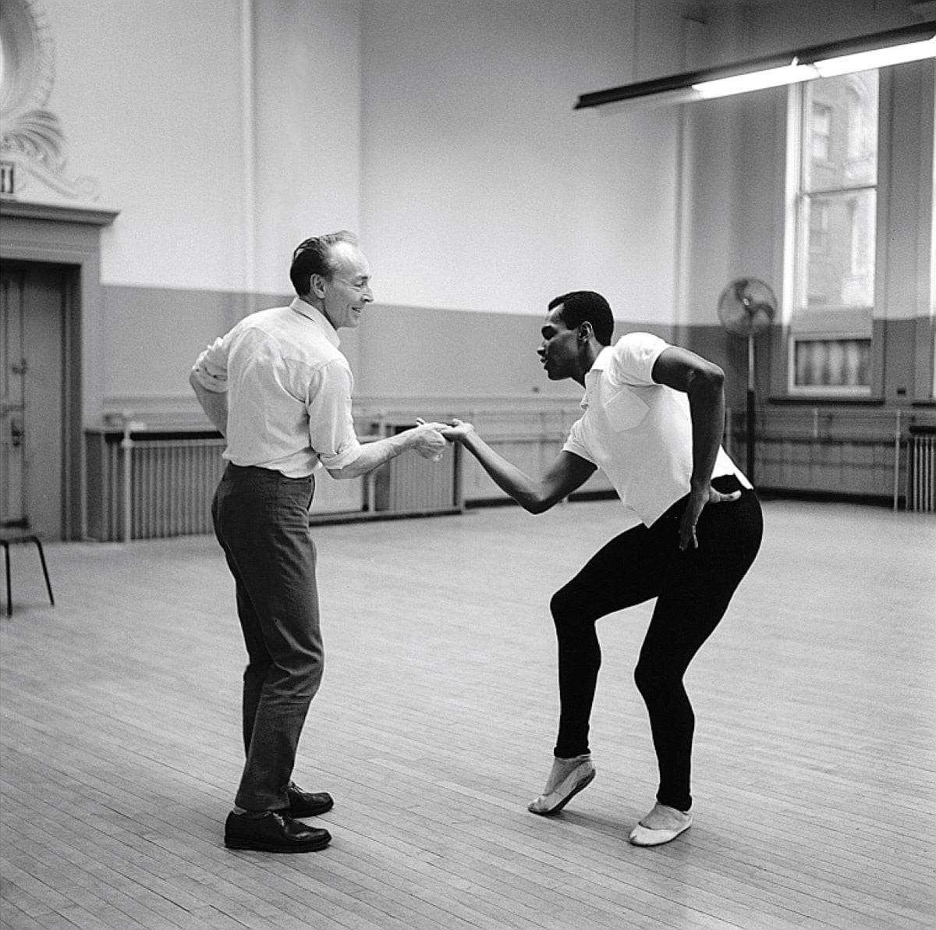

George Balanchine

The Father of American Ballet

George Balanchine is known as “The Father of American Ballet,” but the brilliant and chaotic effects of the international superstar are not only felt in America but throughout the world.

To some, the name Balanchine is quintessentially American, despite his deep Georgian roots. To others, Balanchine is synonymous to modern ballet. Yet to all, the man named George Balanchine remains quite an enigma – an ingenious yet troublesome international dance icon. Although he is mostly credited for founding the New York City Ballet, Balanchine spent a great deal of his career working internationally. For this reason, Balanchine is a central figure in the worldwide dance heritage. The biography of George Balanchine sheds light not only on a brilliant yet difficult man, but also on the ebb and flow of dance movements – his legacy to the world.

George Balanchine’s Childhood, Young Adulthood, & Defection

In the early 20th century, Russia was considered the world champion of ballet, producing technical virtuosos, spectacular performers, and most prolific choreographers of the era. Balanchine was one of those prolific choreographers and a close witness and beloved student of other Russian dance icons. Since his childhood and early adulthood spent in Russia, Balanchine received a unique artistic set of skills. In fact, his challenging, athletic, and musical style were rooted in his earliest training as ballet performer.

George Balanchine was born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Russia, to the iconic Georgian musical composer, Meliton Balanchivadze. Encouraged by his mother and father, he began to pursue arts. He was only five, when he began to study piano, and at the age of ten, he joined the Imperial Theater School of Ballet. From his early training, Balanchine gained his instinctual musicality and practiced world-renowned, comprehensive ballet techniques.

After graduating from the Imperial Theater School in 1921 at 17, Balanchine commenced his career at the Mariinsky Theater, then known as the State Theater of Opera and Ballet. During this time there, he also began choreographing. Before graduation, he set his first piece, a duet called “La Nuit,” performed by himself and a fellow female dancer. After graduation, he continued his musical studies, focusing on piano, counterpoint, harmony, and composition. While performing in Russia, Balanchine would try his experimental choreography that broke away from the classical Russian conventions. That put him in an extremely vulnerable position, as he started receiving threats for continuing doing so.

Subsequently, while touring Europe in 1924, George Balanchine refused to return to the newly created Soviet Union. Alongside him was his first wife, Tamara Geva, as well as Russian dancers Alexandra Danilova and Nicholas Efimov. These four dancers would be seen in London by none other than the great Sergei Diaghilev – the notorious Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes – a launch pad for many world famous dancers and choreographers. Following that, they would all become acclaimed international figures in the world of dance.

Time with the Diaghilev

As Bronislava Nijinsky left the Ballets Russes, impresario Sergei Diaghilev turned his eye to Balanchine. When Diaghilev formally invited him to choreograph for the Ballets Russes, Balanchine accepted. At the young age of 21, Balanchine would become the leading choreographer of the most infamous ballet of the day, and some would argue, one of the most important ballets of all time. As the fifth and final choreographer with the Ballets Russes, he would close out the company’s history.

Over his four years at the Ballets Russes, Balanchine would choreograph crucial works like “Apollo” and “Prodigal Son.” Furthermore, he would develop his trademark neoclassical style. Under previous choreographers at the Ballet Russes, the artform’s romantic traditions had been utterly shattered in the name of avant-garde ideals and modernist thought. Under Balanchine, many conventions would remain broken, but the Romantic-Era themes would return. Balanchine would once again return to the Greco-Roman themes and classical aesthetics, all while keeping the abstraction and experimentation that came before him.

Balanchine’s time with the Ballets Russes was the first real leg of his career, and it was the most critical period in his life. Firstly, this period would establish his neoclassical style, including via two of his most famous works. Secondly, it would facilitate a life-long relationship with the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. Lastly, it would launch his spectacular international career. Nevertheless, although Balanchine’s career had a running start, his future would not be so clear after Diaghilev’s death. For nearly two decades, he would travel across the world in an attempt to find a home and a domain for his choreography.

Forever a Wanderer: Balanchine’s Long Journey

From his early adulthood, George Balanchine’s life had been defined by international travel and immigration. From his departure from the Soviet Union to the founding of the New York City Ballet, his road was long and winding. That, however, is not to say it was useless, as his time abroad bore many fruits.

After Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes passed away in 1929, Balanchine began a series of company launches, collaborations, and choreographies. Almost immediately after the Ballets Russes permanently closed, he began choreographing elsewhere in Europe, most notably in Britain with the Cochran Revues, then with the Danish National Ballet. Shortly afterward, he became the Ballet Master for the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, a company founded by Rene Blum that tried to revive and reunite the Ballets Russes. Once the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo changed leadership, Balanchine left and was replaced by Leonide Massine.

In 1933, Balanchine formed his own company, “Les Ballets,” in Paris. While choreographing with Les Ballets, Balanchine would be seen by Leonard Kirstein, who would be fundamental in the founding of The New York City Ballet. Once he was introduced to Balanchine by Romola Nijinsky, wife of the famous choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky. Leonard Kerstein shared with Balanchine his dream of an American Ballet. Convinced, Balanchine moved to New York, and together they founded The School of American Ballet in 1934, which today is a world-renowned company. One of Balanchine’s most infamous works, “Serenade,” was choreographed for students at the SAB that same year.

Around the same time in 1935, Balanchine and Kerstein created the American Ballet, which, in short, was unsuccessful. Afterward, they were invited by the Metropolitan Ballet in New York City to become the resident ballet later. In 1938, that too fell through due to low funding and artistic differences. Immediately after, Balanchine took his dancers to Hollywood and began working in film. Sometime after that, Balanchine and Kirstein created the American Ballet Caravan, touring the South America. After the tour, the Ballet Caravan disbanded. Once again returning to the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo after Massine left, Balanchine choreographed for the company’s worldwide tours. From 1944 to 1946, the company extensively toured in America; thus, the U.S. became well-acquainted with George Balanchine.

In 1947, Balanchine and Kirstein formed the Ballet Society, a subscription-based performance company aimed at wealthy patrons. After witnessing a performance of “Orpheus,” a wealthy patron Morton Baum invited Balanchine to join the City Center, now known as the Lincoln Center. Finally, the hallmark of Balanchine’s career was solidified and the New York City Ballet was born.

The New York City Ballet: American Ballet, Modernism, & the Cold War

At the age of 43, Balanchine’s choreography had found a home at the New York City Ballet. As Artistic Director of the NYCB, Balanchine choreographed numerous works still performed today across the world. In addition, the NYCB and Balanchine would also become the face of American ballet at home and abroad. Balanchine’s light, speedy pointe work, experimental abstraction, and neoclassical themes would be labeled an American archetype.

While at the New York City Ballet, Balanchine would produce a multitude of famous works, including “Jewels,” “Stars and Stripes,” “Agon,” and “Vienna Waltzes.” While at the NYCB, he continued to explore his neoclassical style and developed it further by creating his signature “leotard ballets” and reworked ballet staples like “The Nutcracker,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “The Firebird” in the Balanchine style. However, while it was a bountiful time for his choreography, it was also a tense time for all, as Balanchine’s time with the New York City Ballet just so happened to coincide with the pinnacle of the Cold War.

As an immigrant from Eastern Europe with deep American patriotism, Balanchine was in a peculiar position as a cultural ambassador. Under the 1958 Lacy-Zarubin agreement, the U.S. and Russia agreed to diplomacy through cultural and educational exchanges. Artists including Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, and Balanchine himself traveled to the Soviet Union and other countries on behalf of the USA.

Consequently, in 1962, the New York City Ballet toured Soviet Russia. Although many thought Balanchine’s work wouldn’t be received well, opinions were mixed. The influence of the Ballets Russes and the Russian technique was found present within his work by the Russian audiences. At the same time, some audience members, accustomed to the linear nature of Russian theater, did not understand the abstract nature of his work. In either case, Balanchine served as a cultural connection between two opposing countries. And this is how Balanchine became a uniting link between the adversaries – the U.S. and the Soviet Union – in such a strained epoch.

The Darkness of Balanchine: Man as Creator & Woman as Created

Although Balanchine’s treatment of women is often overlooked in favor of his genius, it is vital to recognize the effects he had on dance hierarchy. At the New York City Ballet, the male choreographer was the creator and the female dancer was the created.

Balanchine had a habit of marrying his workers; perhaps he picked up the habit from Diaghilev. In the past, he had married Tamara Geva and Vera Zorina, both of whom were often the subjects of his work. While at the NYCB, he had married both Maria Tallchief and Tanquil Le Clercq. Additionally, he also pursued dancer Suzanne Farrel. These women were all prolific dancers in their own right; Maria Tallchief, for example, was the first indigenous American ballerina. Gelsey Kirkland, a famed ballerina, states that Balanchine was a womanizer through and through.

George Balanchine is known for his body image ideals he pushed on his female dancers. To Balanchine, a successful ballerina was thin and as quick as a hummingbird. His influence on women’s weights within the art form, in particular, has had widespread effects on female dancers everywhere and stubbornly persist even past his death.

The Legacy of George Balanchine

Inarguably, George Balanchine’s style was foundational to the American ballet and the contemporary ballet worldwide. His vast body of work is still in modern-day repertoire and can be found from the New York City Ballet to the Bolshoi to the Paris Opera Ballet. Through the lens of Balanchine, we can find connections to points, people, and places in dance history.

Skills and creativity aside, Balanchine spread his teaching methods and beauty standards. The world remembers his influence on the artistic side of dance heritage and his impact on the company culture. After all, George Balanchine cast a large and yet unsurpassed shadow that still looms over the American ballet today.

Archil Gurieli-Chkonia

Archil Gurieli-Chkonia was born in 1895 to the family of a petty nobleman in Georgia. He claimed that his grandmother was a descendant of the Gurieli princes, which was the reason why he added this surname to his official name, later receiving the title of “Tavadi” (prince). In 1921 Archil Gurieli-Chkonia emigrated from Georgia. First, he travelled to Austria, and then moved to France. Then, in 1937, he immigrated to the United States. In 1945-1947 he headed the Georgian Society of America. He never forgot his relatives and always helped them throughout his life, including via letting some of them receive their education abroad.

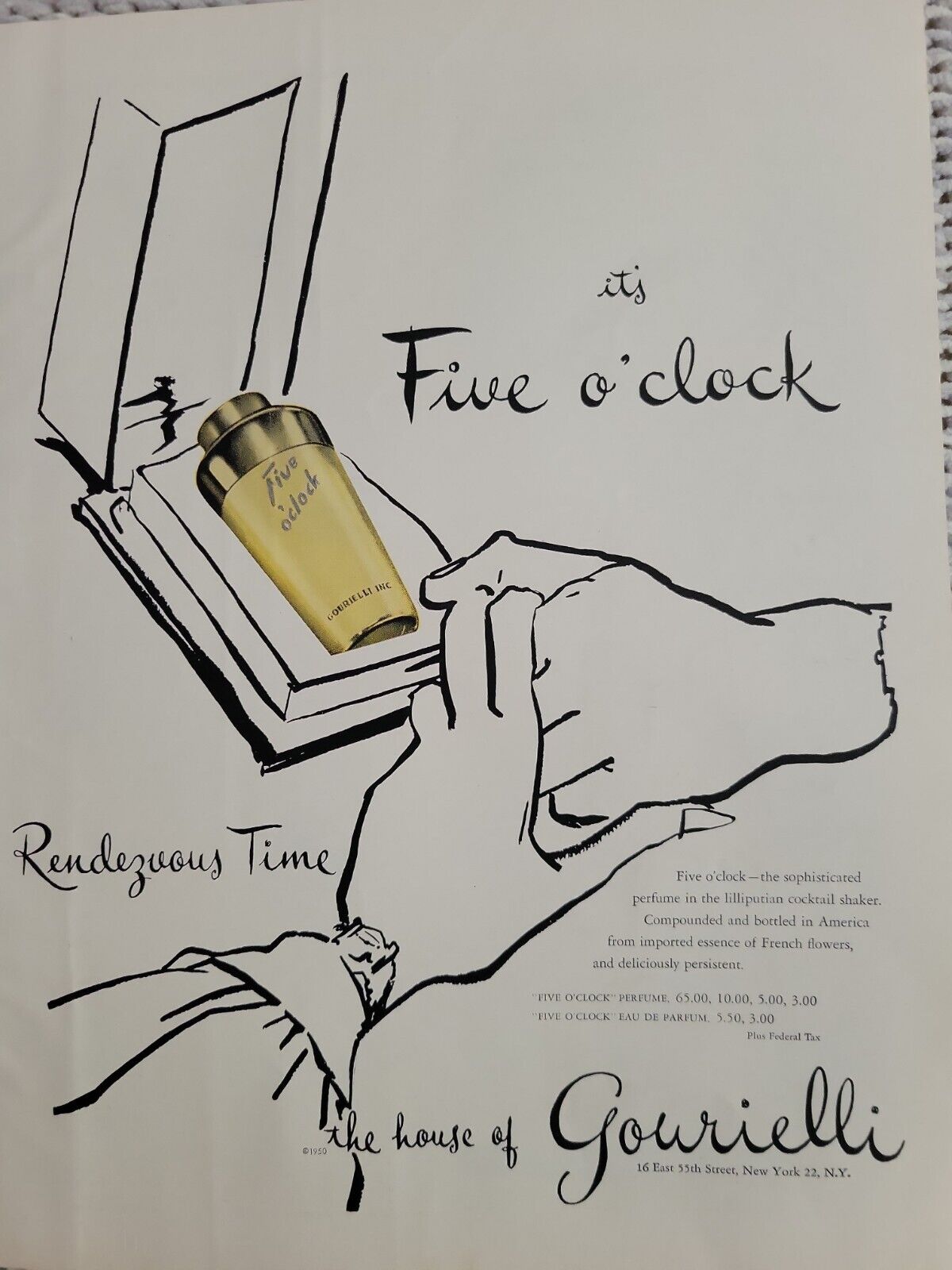

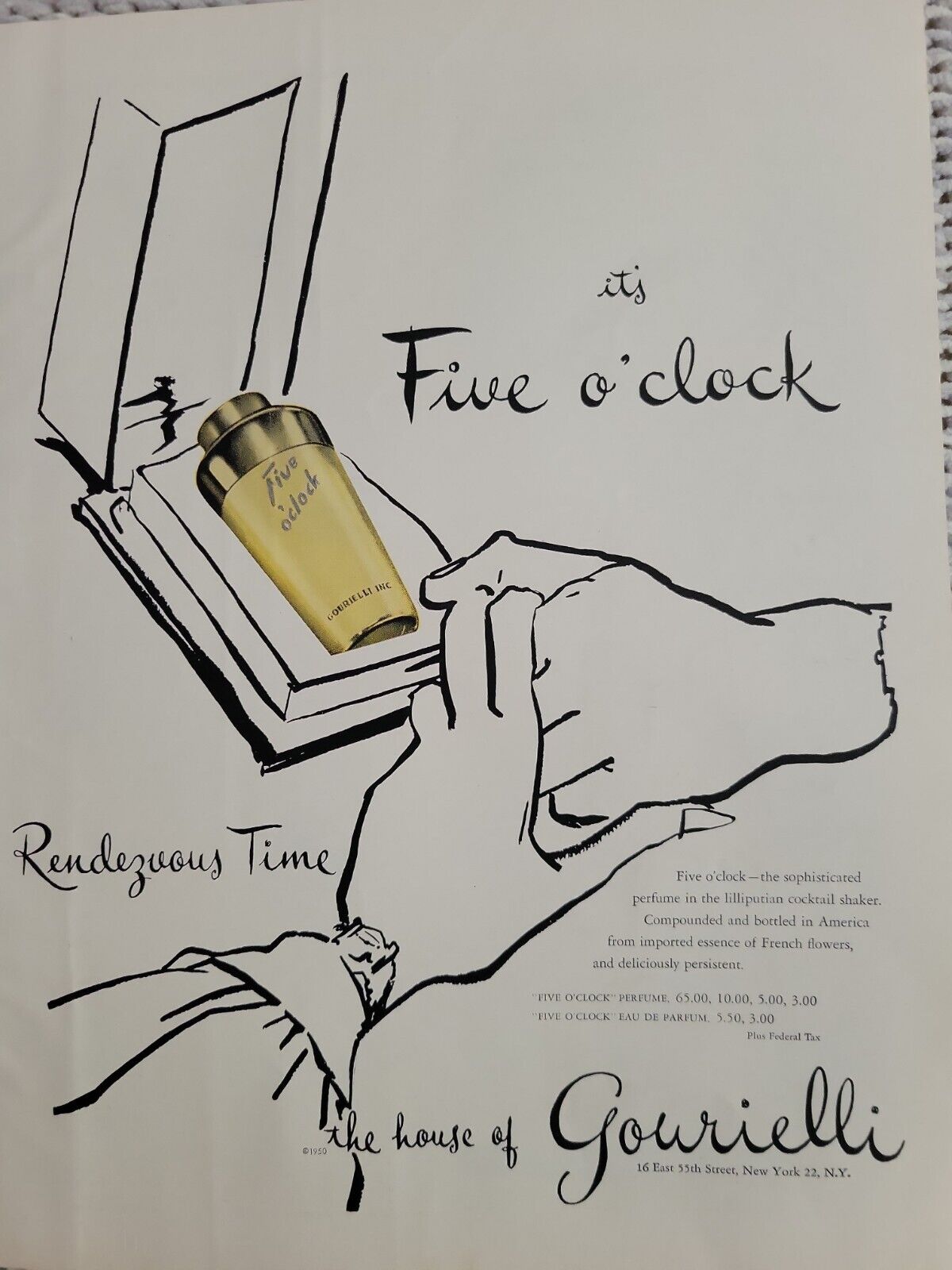

Archil Gurieli-Chkonia found himself at the center of wide public attention, when he married one of the richest women in the world, American business woman, art collector and philanthropist, Helena Rubinstein (1882-1965), who was also dubbed the Queen of Cosmetics. Helena was of Jewish descent and was born in Poland. She owned one of the biggest cosmetics companies in the world called ‘Helena Rubinstein’, which now forms part of the L’Oreal Group. Rubinstein led an active public life and was the patron of art. Her company has built the Museum of Modern Arts in Tel-Aviv. She gave money to traveling artists and Jewish students, funded various scientific researches, and played an important role in the America-Israel Cultural Foundation.

The family life of Helena Rubinstein and Archil Gurieli-Chkonia was subject to endless rumors, as Helena was 23 years older than her husband. However, as it seems, they were happily married and very attracted to each other. Furthermore, Helena and Archil had created quite a successful business together and laid foundation of the Gurieli Apothecary line. They produced expensive cosmetics both for men and women. Their firm’s Paris salon was led by Gurieli’s sister, Mariam, who had been a designer of hats for the world famous Coco Chanel.

The couple led a bohemian life style. Among other things, they shared the same hobby – playing the card game of “Bridge.” Gurieli was a very good player and often won considerable sums of money. Besides, their family stood out for their great hospitality and generosity. Archil Chkonia-Gurieli, thanks to his good manners, good looks and good humor, acquired new friends very quickly. He had befriended many famous names, including renowned actors Errol Flynn and Gregory Peck as well as writers Janet McDonald, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce and others.

Archil Gurieli-Chkonia died in 1955, in Manhattan, New York. Helena was devastated, but outlived her husband by ten years. Gurieli-Chkonia left no offspring and all of his property, according to the marriage contract, was passed on to Helena.

George Coby

George Coby / The First Georgian Millionaire in America & The King of America’s Chemical Industry

Grigol was born in 1883, in the village of Tkhmori, to a peasant family. He received his primary education from the village priest. When he turned 10, he left home and headed to Borjomi, where he joined his older brother at a glass factory. He spent 4 years working there. His diligence quickly brought him authority and he rapidly got to know every technique employed by the factory in great detail. He also revealed a knack for invention, coming up with a way to significantly boost the factory’s output. The owner of the factory, a German by the last name of Schumann, introduced the young man to the owner of Borjomi, Mikheil Mukhran-Batoni himself. After receiving numerous accolades and a stipend, Grigol was sent to the Krasnodar province, to work at the Konstantinovka glass factory. It was there that he met Dasha Nodvikova, whom he later married.

He was the Georgian king of construction technology who invented super-hard glass blocks and water-resistant concrete used for building skyscrapers.

In 1907, Kobakhidze moved to Germany and later to Britain. By 1909 he was already in America, where an association of fellow countrymen helped the 26-year-old newcomer find a job. He spent 9 years working for General Electric, accumulating capital. He did not abandon his inventive habits, patenting several fountain pens. He had a small business selling these pens, along with other stationery. In 1919, he founded a large factory in the city of Attleboro, Massachusetts. By 1922, Coby Glass Products Company had firmly established itself among the top industrial players of the Eastern United States. In 1929 its turnover comprised $15 million (today’s equivalent of $204 million) with an annual income of $4 million ($54 million).

Grigol’s company manufactured medical, chemical, construction and 45 other types of goods as well as raw materials. The products were considered among the best due to his employment of constantly improving technology. Despite his status as a millionaire, Grigol was far from resting on his laurels. He patented more than 60 inventions and techniques, which brought his company even more prestige. A special order by Giorgi Machabeli (the famous American perfumer of Georgian origin, Prince Matchabelli) only served to magnify Grigol’s success – a perfume flask, shaped in the likeness of Georgian Queen’s personal insignia – a golden wreath with a small cross on top. Aircraft designer Alexander Kartvelishvili’s, also known as Alexander Kartveli, order of heavy-duty glass for pilot cockpits was also noteworthy.

Grigol, however, wasn’t all about business. He was obsessed with restoring Georgia’s independence by returning there and serving his country. However, in years 1919-1921 his business was just taking its first steps. After the Soviet Union annexed Georgia, he didn’t abandon the idea of helping his country, offering the Kremlin a giant glass factory project which would allow many Georgians to become employed. He was asked to provide an investment in advance, but he refused, not trusting the Bolsheviks with his money. They did not agree to let him oversee the project personally, as he originally intended, so he was forced to abandon the idea.

He returned to Georgia anyway in 1925, retracing the path that he walked as a boy 33 years prior. He built a house for a family who let him stay for the night and took care of him. He brought his mother gifts worth $10,000, just as he had promised. He helped many families in need, built a school and a pharmacy for his native village, erected two bridges over the river, repaired a church and provided traders with goods. But very soon his nephew arrived from Tbilisi bringing news about Bolsheviks declaring a manhunt for him, so he had to flee both his native village and the country.

“In 1925 the Georgian chemist was considered to be one of the richest men in the U.S. At that time, George Coby was unanimously named “King of the American Chemical Industry.”

Two of Coby’s greatest inventions were water-resistant concrete and super-hard glass block. In the beginning of the 1920s he came up with a formula for concrete that resisted the erosion caused by moisture. Later he introduced some radical changes to the composition of an ordinary brick, creating a glass block, which proved perfect for covering buildings, since it gave them a reflective sheen. These two inventions transformed the American construction industry. In the 1930s they were used on the Chrysler Building, New York City’s famous skyscraper.

Needless to say, this made George Coby a multimillionaire. In 1925, the Georgian chemist was considered to be one of the richest men in America. At that time, George Coby was unanimously named “The King of American Chemical Industry.”

When the U.S. joined the Second World War in 1941, Grigol asked the government for financial assistance to restore his business. After a brief analysis of his crumbled empire, he was given a license and two million dollars, which allowed him to not only rebuild and re-launch his factories but to become even richer than he was before. Remarkably, the first thing he did with his newfound (for the second time now) wealth was to open a toy store and a network of soup kitchens to feed the homeless.

“Boxes bearing the colors of the Georgian flag had an inscription ‘Coby. Glass Christmas tree ornaments. ‘Christmas is Coby!’ written on them in both English and French, since they were shipped to Canada as well”

After the war, he came up with new inventions – electric candles and twinkling lights. Filled with colored liquid, garlands of tiny lamps lit up, pulsated and moved when plugged into an electric socket. Back then, Christmas trees were adorned with real candles, which frequently caused fires, so his invention instantly found demand. Later on he began making lamps and candles out of colored glass, ending the need for colored liquid and making them even safer. He also utilized colored glass for toys of various shapes, naming them ”ornaments”. These toys frequently bore Georgian motifs, such as grapes or grapevine leaves. Boxes bearing colors of the Georgian flag had an inscription: “Coby. Glass Christmas tree ornaments. ‘Christmas is Coby!’ written on them in both English and French, since they were shipped to Canada as well.

Grigol Kobakhidze didn’t have any children and Soviet repression exterminated almost all of his relatives. He refrained from contacting those who remained, afraid that it would bring about more repression. Since he couldn’t find any Georgians who would be interested in his business, he chose the Paglia brothers from Italy as business companions, who ended up continuing his work after his death.

George Papashvily

American writer and sculptor of Georgian origin

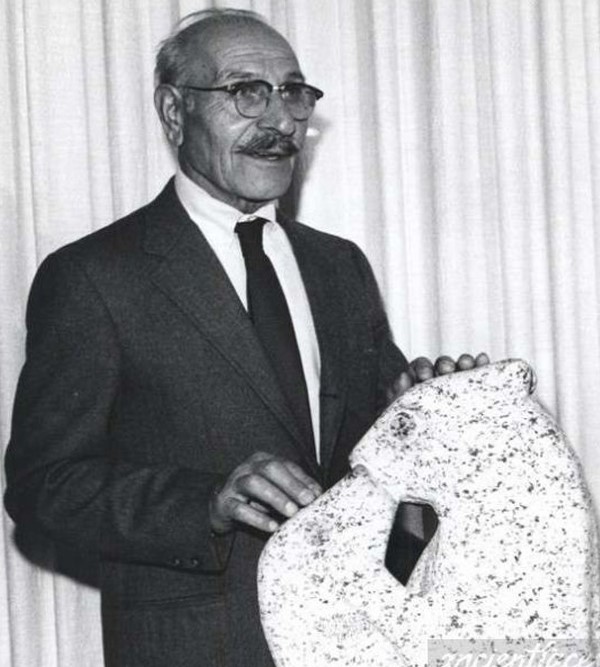

George Papashvily (Georgian language: გიორგი პაპაშვილი August 23, 1898 – March 29, 1978) was a Georgian-American writer and sculptor. One of the most famous Georgian émigré artists of the 20th century.

George Papashvily was born in the village of Kobiaantkari in the Dusheti District, Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of eastern Georgia. According to his autobiography, he apprenticed as a sword maker and ornamental leatherworker. After serving as a sniper in the Russian army in the World War One, he immigrated to America in the early 1920’s, and thereafter lived and worked in the U.S. Papashvily succeeded both as a sculptor and as an author. He was also a gifted engineer and inventor.

The story of George (Giorgi) Papashvily starts in 1921, just before the Soviet regime was established in his native Georgia. By then a 23-year old soldier, Papashvily sailed from the port of Batumi to Constantinople, current Istanbul. Then his fate brought him from Constantinople to America, a dreamland where his life has turned into a great tale.

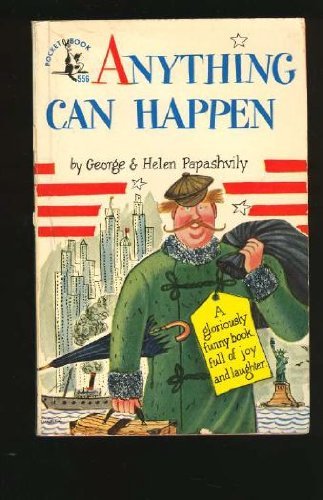

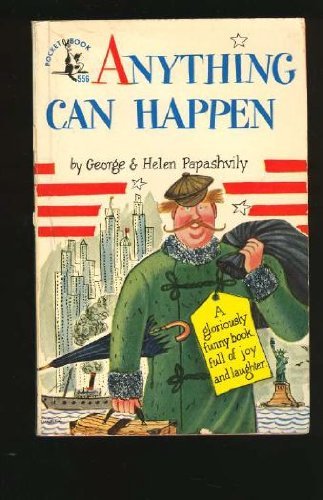

Later, his book about Georgia and emigration, written in English and titled “Anything Can Happen,” became a bestseller in America. His 1940’s book sold 1.5 million copies worldwide, and it has been translated into 15 languages. In 1950, George Papashvili book made it to the list of America’s 50 Favorite Literature Works alongside Jack London, Eugene O’Neill, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and other iconic writers. In 1952, George Seaton, a winner of two Academy Awards and one of Hollywood’s most renowned film producers and directors, who later presided over the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, Writers Guild of American West and the Screen Directors Guild, created a movie under the similar title. The film received and won in the nomination of the “Best Film Promoting International Understanding” and was subsequently awarded the “Gold Globe” at a film festival held in Los Angeles, California.

Papashvily’s famous book tells the stories – in a very light and amusing fashion – about his native village Kobiantkari; his relatives; emigration; the reality of self-assertion by immigrants in America.

Papashvily also wrote other books, some of which are as follows:

- Yes and No Stories – A Book of Georgian Folk Tales (1946)

- Dogs and People (1954)

- Thanks to Noah (1956, has become part of must-read literature curricula in U.S. universities)

- Home and Home Again (1973, recounting a trip they made back to the village in the 1960s)

- Russian Cooking (1969)

George Papashvili has been little-known in Georgia so far. While all American editions mention George Papashvily as “American writer and sculptor of Georgian origin,” his writings have not yet been considered part of a huge immigrant literature tradition in Georgia.

George Papashvily as a Sculptor

In addition to becoming a great writer, George Papashvili also happened to be a renowned sculptor. His works were exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the University of Philadelphia, and etc. Arthur Stenius, who owned a large documentary corporation in the U.S., made a documentary on Papashvili as a sculptor called “Beauty in the Stone”

“I went in the barn, and took a piece of chestnut. I’ll start with an animal, I thought a sheep, can’t go wrong with a sheep. I started carving and so far, I have never stopped” – George Papashvily, on creating his first sculpture.